Killers of the Flour Bin

A tale of costly eggs, sweet buns and a medical sleuth in 19th-century Philadelphia

As American consumers and the food industry continue to eye egg prices with concern and suspicion, this historian of lead poisoning would like to make a modest proposal, a proposal made all the more feasible by recent actions of the federal government to rid the American food industry of burdensome regulations. Just follow the lead of creative and cost-conscious bakers in Philadelphia the 1880s.

In the five years since Louis Diebel moved into Kensington, a working-class neighborhood in northeast Philadelphia, his family of seven—Louis, his wife, and five children—had grown by two. At the end of 1886 the Diebels were feeding seven children, aged 14 months to almost 14. The family’s favorite breakfast was tea buns. Each day they purchased a dozen or so from the baker who had recently set up shop in their neighborhood. Two dozen on Sundays. Louis wasn’t fond of sweet cakes, but for everyone else, even the baby, each day began with the sweet buns, washed down with coffee or milk.

Around Christmastime, five-year-old Mary developed a mild case of whooping cough. After about a week she lost her appetite and grew nauseous. Assuming her symptoms were related to the cough, the parents didn’t seek medical attention. Then, on January 8, Mary was overtaken by wracking convulsions that continued until her death the next morning. Two days later Mary’s little sister Louisa developed a similar mild cough. For two weeks she continued to eat and play as usual. Then, on the 23rd she became nauseous. Nausea gave way to seizures, and death followed twelve hours later.

The day Louisa died, baby William, who also had been coughing, began having mild convulsions. At this point, a young physician from Jefferson Medical College’s medical clinic was brought in. David Denison Stewart, 29, had recently been promoted Chief of the clinic. He carefully monitored William’s harrowing progress over the next two days as he passed in out of convulsive episodes. But the baby did not die. After three days it looked like he was out of the woods. A week later, on February 3, he suffered one more major seizure. After that, Stewart reported, William quickly recovered.

But the Diebels’ ordeal did not end with William’s return to health. For the next three months, Stewart carefully recorded in the cold clinical language of the physician-scientist the symptoms and outcomes—and autopsy results—as seven-year-old Louis Jr. succumbed in March, the family’s house servant developed convulsions, 12-year old Amelia sickened and died, and the two other Diebel children sickened but survived.

In Stewart’s time medical science was nearly impotent against infectious diseases and the overwhelming burden in death and debility they imposed. Naturally, then, he focused on the fact that whooping cough had preceded the onset of headaches and convulsions in all the sickened members of the Diebel household. Or at least he did so until Amelia’s death in mid-May. Amelia had not been sick—no coughing or other illness. Stewart recorded that “she had fallen off in flesh and color” which the parents speculated was due to “her grief on account of the loss of her brother and sisters.”

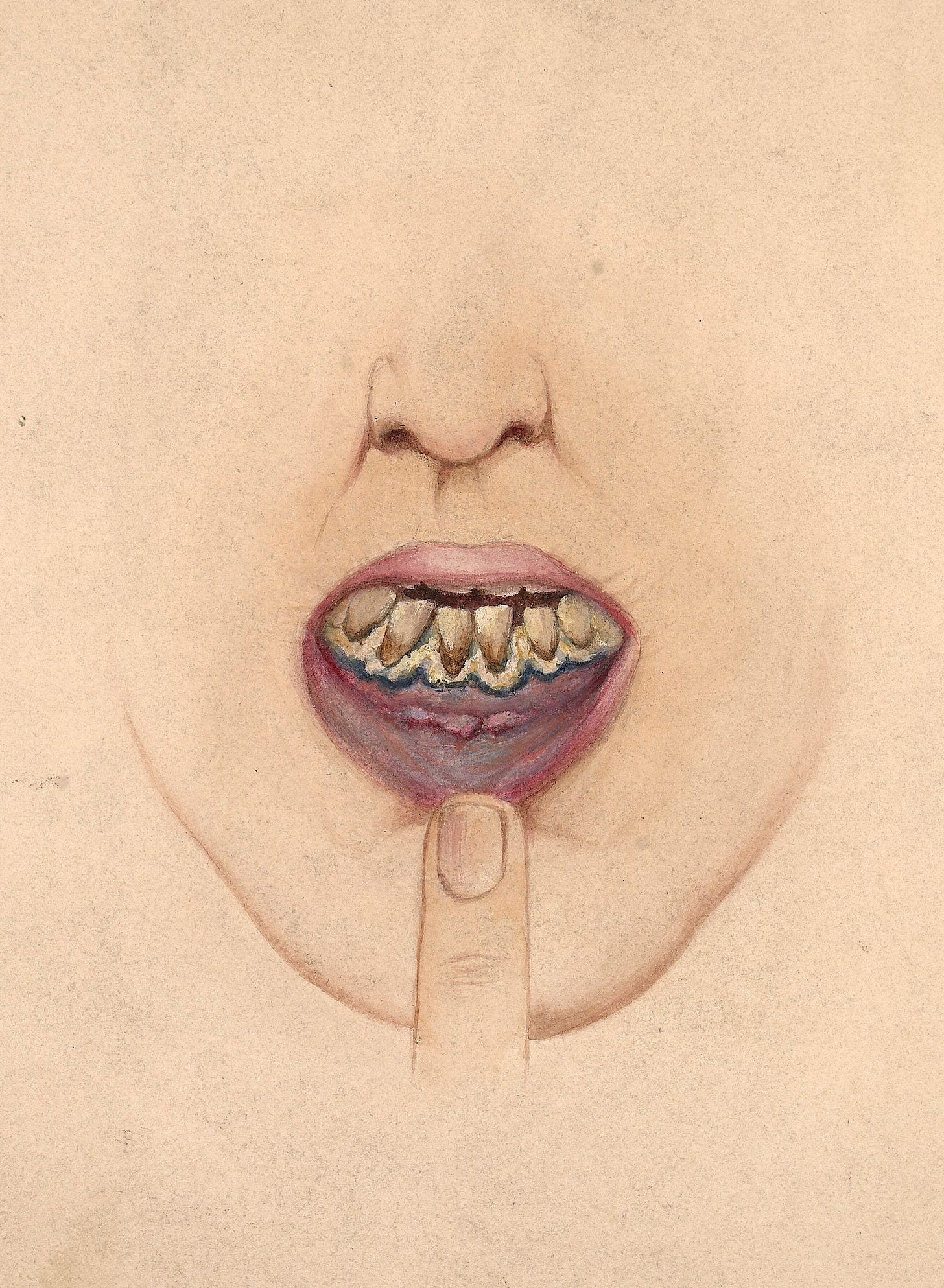

Stewart began to suspect that perhaps the coughs might have little or nothing to do with the constellation of symptoms accompanying the convulsions. When a sixth Diebel child, thirteen-year-old Kate, began to show signs of illness, he carefully catalogued her symptoms, from photophobia, yellowish skin, mild fever and an “over-acting” heart, colicky pains and growing constipation. These symptoms, Stewart reported, “assisted materially in throwing light upon all the preceding cases.” They were all symptoms he might have seen in sick workers from lead-using trades. Suspecting lead poisoning, he examined Kate’s gums for what was considered the gold standard for lead poisoning diagnosis, the blue line of lead sulphide so frequently found in the mouths of known lead poisoning victims. And indeed she had “a moderately well-marked” blue line along two lower left teeth. In that moment the Diebel family’s case exited the realm of infectious disease and slid into toxicology and environmental health.

Stewart began the search for a source of lead. Nothing in the home’s plumbing seemed suspicious. A new kettle, presumably lead-glazed, seemed unlikely to have contributed much lead. No, he became convinced the lead had to have come “from a source external to the house.” Apart from the kettle, the only new factor in the home was those sweet buns the children loved so, bought from the baker who had set up shop nearby the previous year. Stewart set out to visit the baker, George Palmer, and found his wife to be suffering from all the classic symptoms of lead poisoning, from constipation to fetid breath to lead lines on her gums “of a deep blue color.” He immediately determined that Mrs. Palmer was “intensely poisoned by lead.”

Palmer said he couldn’t say how his wife could have become poisoned “as he had no lead about his establishment.” But Stewart insisted the baker allow him to inspect his cellar. There he found a pitcher filled with a “yellowish substance, partly in solution,” which Stewart recognized as chrome yellow, or lead chromate. Palmer said he was unaware of the pigment being poisonous. He used it as an egg substitute in his cheaper products; he used real eggs only in his more expensive cakes. From here the plot thickens with horrific details. The reason Palmer had moved to the new neighborhood was the scandal surrounding the suspicious deaths of his first wife and five of their nine children. Neighbors suspected he had acted from “a desire to rid himself of the burden of supporting so large a family report,” but backed off when the baker and his 24-year-old son became gravely ill with the same symptoms as had felled his wife and children. His son died, but Palmer recovered, remarried, and moved to Kensington to start over.

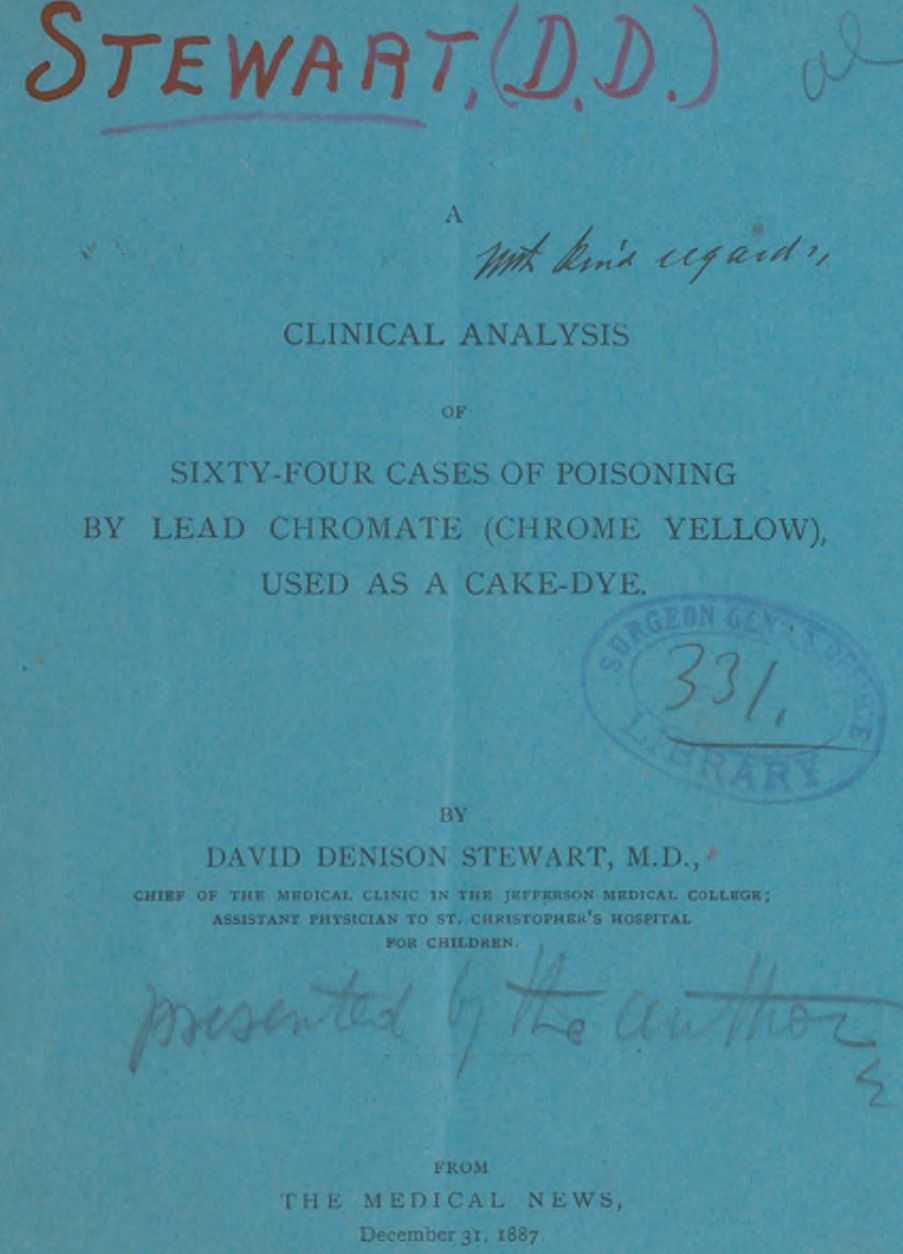

Stewart’s investigations did not stop with the Palmers. He ended up writing up reports on a total of 64 cases of lead poisoning from adulterated foods in the Philadelphia area.

But for us, at this point, our attention turns from shoe leather epidemiology to the criminal justice system.

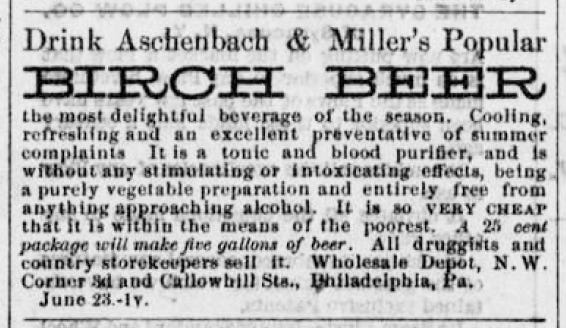

In June, the coroner called for the exhumation of the bodies of all four Diebel children as well as Palmer’s wife and five children. Chemical analyses led to a coroner’s inquest in the case of Palmer’s two adult children and two of the Diebels. At the inquest Palmer testified that for five years he had been using chrome yellow, sometimes called “confectioner’s yellow,” adding it to “cinnamon buns, doughnuts, Dutch cake, and tea buns.” He bought the pigment two pounds at a time, at 30 cents a pound, from a baker’s supply house. That vendor, August Zippelius, testified next. He said that other bakers in the city used the lead pigment, which he purchased from Aschenbach & Miller, a large drug and paint company. That may sound off to readers today, but it was standard practice well into the twentieth century for chemical supply firms to deal in both paints and drugs. Aschenbach & Miller advertised everything from cocoa to birch beer to sulphur soap. Dr. Adolph W. Miller, of Aschenbach & Miller, was called to testify. His firm had indeed sold lead chromate to bakers. He estimated that 80 percent of the city’s bakers used chrome yellow.

The jury determined that the four deaths were, as suspected, caused by lead chromate in Palmer’s baked goods. And while they found that Palmer had acted out of ignorance, “severe censure” was due to Zippelius, “who circulated recipes containing chromate of lead, knowing that it was a…deleterious substance.” The druggists, Aschenbach & Miller were also censured for “carelessness in furnishing bakers with this substance knowing that it was to be used in food.”

In the end, the inquest referred the baker’s supply dealer, Zippelius, to the American Society for the Prevention of Adulteration of Food, which brings us, at last, to the regulatory side of this story—the birth of the food safety system that percolated up from cities and states in the late 19th century, to find a national power in the 1906 federal Pure Food and Drug Act, launching over a century of science-driven, never-perfect, but determined bureaucracy charged with keeping lead out of buns and meat plant laborers out of Durham’s Pure Leaf Lard. No longer was the detection of adulterated food to depend on savvy physician-scientists like Stewart reacting after the fact to horrific accidents or criminal behavior. The PFDA was explicit about chrome yellow. Section 7 spells out the definition of “adulterated,” specifically in the case of confectioneries, deemed adulterated if they contain “terra alba, barytes, talc, chrome yellow, or other mineral substance or poisonous color or flavor…”

Just because chrome yellow was to be kept out of food didn’t mean we were done with it. Even after federal law in the 1970s banned lead paint in home interiors, the durable and inexpensive pigment continued its traditional role of providing its cheery hue to the iconic American school bus, “yellow cabs,” and the bright yellow lines down the center of the streets they traveled. At least the bans extended to the yellow pencils found in the notebooks and desks of children or chewed by anxious students. If I may be permitted a small tangent on the pencil question: the “lead” in lead pencils is not lead, but non-toxic graphite (historically misnamed “black lead” or “plumbago.”)

And so we arrive back at the high price of eggs. Although Health and Human Services Secretary Robert Kennedy Jr. has expressed his desire to go after all artificial coloring in food, his Commissioner at the Food and Drugs Administration, Martin “Marty” Makary, may have difficulty enforcing any new prohibitions his boss imposes, what with DOGE shutting down offices and firing thousands of the agency’s professionals. This chaotic moment presents a splendid opportunity for bakers—whether small operators in the tradition of George Palmer or more formidable firms like Little Debbie. Now they are free once more to cope with high egg prices with a little help from modern technology. A few clicks will take them online to order as much as they like from Chinese vendors like Alibaba.com. Even with the liberation tariff, this option will be cheaper than eggs.

For more ripping yarns from the history of lead poisoning, check out Brush with Death: A Social History of Lead Poisoning.

Terrific piece!